Monitor soil moisture levels before operating heavy equipment—compaction damage increases exponentially when soil contains more than 80% field capacity, particularly in Alberta’s clay-rich soils. Use a simple penetrometer or squeeze test to assess readiness: soil should crumble in your hand rather than form a sticky ball.

Apply controlled traffic farming patterns to limit the footprint of machinery passes across your fields. Designating permanent wheel tracks reduces compacted areas by up to 70% compared to random trafficking, while concentrated weight on specific paths allows for targeted remediation rather than field-wide treatment.

Adjust tire pressure to match load requirements and soil conditions—reducing pressure to 12-15 PSI on tractors and combines distributes weight across a larger surface area, decreasing pressure per square inch by 30-40%. Track systems offer even better weight distribution on sensitive soils.

Time deep tillage operations strategically when remediating compacted layers. Break up hardpan during freeze-thaw cycles in early spring or late fall when natural forces assist mechanical disruption, and soil shatters rather than smears. Follow with cover crops like daikon radish or forage turnips that drive biological pores through compacted zones year-round.

Understanding how compaction restricts water infiltration and root penetration transforms your approach to field management. Each pass of heavy equipment under poor conditions can reduce yields by 5-15% for multiple seasons, but implementing proper techniques protects your soil structure, optimizes water-holding capacity, and maintains the productive potential that makes Alberta agriculture thrive.

Understanding Soil Compaction and Water Movement

The Soil-Water Connection

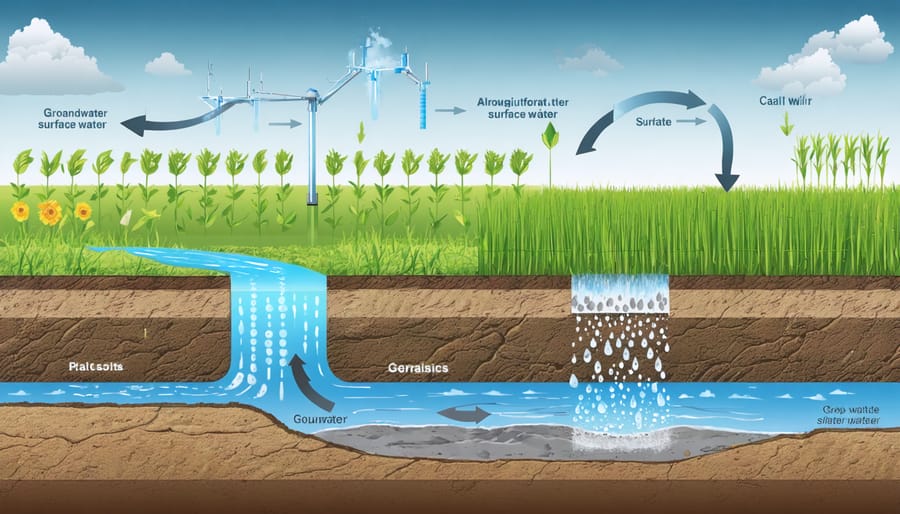

Understanding the relationship between soil structure and water movement is fundamental to making informed decisions about compaction management on your farm. Think of soil as a network of interconnected spaces—when soil particles arrange themselves properly, they create pores of various sizes that act as both storage tanks and highways for water.

Soil pores come in two main categories. Macropores, the larger spaces between soil aggregates, allow for rapid water infiltration and air movement. Micropores, the smaller spaces within aggregates, hold water against gravity, making it available for plant roots. A healthy soil maintains a balance between these pore types, typically aiming for around 50 percent pore space in agricultural soils.

When compaction occurs, soil density increases and total pore space decreases dramatically. More importantly, the macropores collapse first, severely restricting water entry and drainage. Dr. Tom Bruulsema from Alberta Agriculture notes that compacted zones can reduce infiltration rates by 60 to 80 percent compared to well-structured soil.

This compression doesn’t just slow water down—it fundamentally changes how water moves through your soil profile. Compacted layers create barriers that cause water to pond on the surface or move laterally rather than downward, leading to uneven moisture distribution. During Alberta’s intense spring rains or sudden summer storms, these compacted zones can mean the difference between water reaching your crop roots or running off your fields, taking valuable topsoil with it.

Signs Your Soil is Over-Compacted

Recognizing over-compaction early helps you take corrective action before yield losses become significant. Standing water after rainfall is one of the most visible indicators – when water pools on your field for extended periods, it signals that compaction has reduced infiltration rates and created barriers to drainage. This is particularly common in Alberta’s clay-rich soils following wet spring conditions.

Walk your fields and examine root systems by carefully digging up plants. Stunted, horizontal root growth or roots that abruptly change direction indicate a compacted layer restricting downward penetration. Healthy roots should extend straight down with lateral branching. Poor or uneven crop emergence across your field, especially in wheel tracks or headlands, often reveals compaction problems beneath the surface.

Visual surface cues include cracked, crusted soil that’s difficult to penetrate with a spade, and areas where equipment creates deep ruts that persist between seasons. You might also notice reduced earthworm activity – these soil engineers avoid heavily compacted zones. Alberta agronomist Karen Mitchell notes that “farmers who regularly monitor these indicators catch compaction issues two to three years earlier than those who wait for obvious yield impacts.” If you’re observing multiple signs simultaneously, it’s time to assess soil density and consider remediation strategies suited to your operation’s specific conditions.

Strategic Compaction: When and Why It Matters

Seedbed Preparation and Soil-to-Seed Contact

Proper seedbed preparation through controlled compaction plays a crucial role in successful crop establishment across Alberta’s diverse growing regions. When you apply the right amount of pressure during seeding, you create intimate contact between seeds and soil particles, which directly improves moisture transfer to the seed coat and triggers faster, more uniform germination.

The key is finding that balance between adequate firmness and avoiding over-compaction. Light to moderate pressure from seed press wheels or packing equipment helps eliminate air pockets around seeds while maintaining enough pore space for water infiltration and root emergence. Research from Alberta Agriculture shows that optimal seed-to-soil contact can advance germination by 2-3 days and increase emergence rates by 15-20 percent compared to loose seedbeds.

Alberta farmer James Peterson from Lethbridge County reports significant improvements after adjusting his press wheel pressure settings. “We noticed more even stands and better early vigor once we started monitoring our downforce,” he explains. “The crops emerged more uniformly, especially in our drier fields.”

For best results, ensure your seedbed is level and free of large clods before seeding. Adjust packing equipment based on soil moisture—drier conditions typically require slightly more pressure, while moist soils need a lighter touch to prevent crusting.

Capillary Action and Moisture Conservation

Achieving the right level of soil compaction creates an optimal balance for water movement in your fields. When soil particles are properly arranged through controlled compaction, they form capillary channels that act like tiny straws, drawing moisture upward from deeper layers during dry periods. This natural process becomes especially valuable during Alberta’s summer months when rainfall can be scarce.

For prairie soils, maintaining bulk density between 1.2 and 1.4 g/cm³ typically provides the best conditions for capillary action. At these levels, pore spaces remain connected enough to facilitate upward water movement while still allowing excess moisture to drain away during wet periods. This dual benefit supports consistent soil moisture retention throughout the growing season.

Agricultural specialist Dr. Maria Chen from Lethbridge Research Centre notes that farms using strategic compaction techniques observed 15-20% improvements in plant-available water during drought conditions. The key lies in avoiding over-compaction, which crushes these beneficial capillary pathways and prevents both upward moisture movement and downward drainage. Regular monitoring with a penetrometer helps ensure your soil maintains this productive sweet spot where water moves freely in all directions as crops need it.

Effective Compaction Techniques for Alberta Farms

Roller Packing and Press Wheels

Roller packing and press wheels offer precise compaction control during seeding operations, making them particularly valuable for Alberta’s diverse soil conditions. These tools create firm seed-to-soil contact while maintaining adequate air spaces for germination and root development.

Press wheels mounted directly on seeding equipment typically weigh between 23 and 45 kilograms per row unit. For lighter soils common in central Alberta, lighter pressure around 23 to 30 kilograms works well, while heavier clay soils may benefit from 35 to 45 kilograms of pressure. The key is achieving consistent seed depth without creating a compacted layer that restricts root penetration.

Packer rollers, which follow behind seeding equipment, come in various designs including steel, rubber, and cast iron configurations. Steel packers work effectively in drier conditions, while rubber models provide gentler compaction suitable for wetter soils. According to soil specialist Dr. Maria Chen from Olds College, “The goal is compacting just enough to eliminate large air pockets around seeds without creating a crust that prevents emergence.”

Target soil moisture sits between 50 and 70 percent of field capacity for optimal packing results. Working soil outside this range either creates excessive compaction when too wet or provides insufficient firmness when too dry. Many Alberta producers test moisture by squeezing a soil ball – it should hold together but crumble with light pressure.

Adjust packer weight and down-pressure based on real-time soil conditions rather than maintaining constant settings throughout seeding season, ensuring consistent emergence across varying field zones.

Controlled Traffic Farming (CTF)

Controlled Traffic Farming (CTF) represents a strategic shift in how you manage field traffic, designating permanent lanes where all machinery travels while keeping the rest of your soil untouched. This approach can reduce the compacted area of your field from as much as 80% down to just 15-20%, dramatically improving soil structure in your growing zones.

The system works by using GPS guidance to ensure tractors, combines, and sprayers follow identical wheel tracks year after year. In Alberta’s diverse growing conditions, farmers implementing CTF have reported water infiltration rates improving by 30-50% in the traffic-free zones, with corresponding increases in crop yields ranging from 10-15%.

Setting up CTF requires careful planning around your equipment. Start by standardizing axle widths across your machinery fleet, or consider using controlled width implements that match your existing traffic pattern. Many Alberta producers find success beginning with their primary field operations, like seeding and harvesting, before expanding to include all field passes.

The investment pays dividends beyond compaction management. Reduced soil disturbance means better moisture retention during dry periods and improved drainage during wet springs, both critical for Alberta’s variable climate. One central Alberta grain farmer shared that after three years of CTF implementation, his fields showed measurably better water holding capacity and required fewer passes to achieve ideal seedbed conditions. The permanent traffic lanes also become more stable over time, reducing fuel consumption and equipment wear during field operations.

Timing and Soil Moisture Considerations

Timing your compaction activities correctly can make the difference between building soil structure and causing lasting damage. The key factor is soil moisture content – specifically, working within the optimal range between field capacity and the plastic limit.

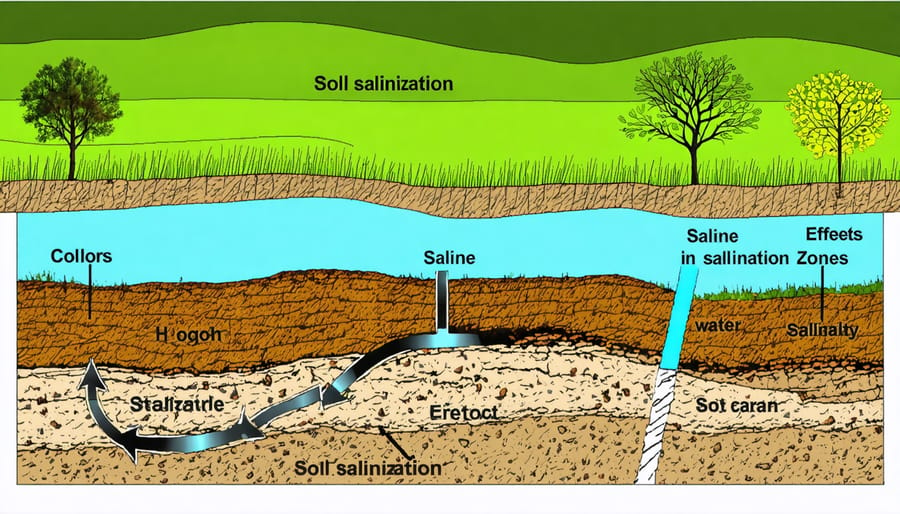

Soil at or near its plastic limit becomes moldable and sticky, much like clay in a potter’s hands. Compacting at this moisture level creates dense, brick-like layers that restrict root growth and water infiltration for years. For Alberta’s predominant clay loam soils, this typically occurs when moisture content exceeds 20-25% by weight.

The ideal window for compaction work is when soil is slightly moist but friable – breaking apart easily in your hand. A practical field test: squeeze a handful of soil. If it forms a ball that crumbles with light pressure, conditions are suitable. If it forms a sticky ball or ribbon, wait for drier conditions.

Spring fieldwork poses particular challenges in Alberta. After snowmelt, allow fields adequate drying time before operating equipment. Dr. Anne Smith from Olds College notes that rushing spring operations on wet soils causes more compaction damage than any other factor on Prairie farms.

Consider implementing effective water management strategies to monitor soil moisture levels consistently throughout the growing season, helping you identify optimal timing for necessary field operations.

Equipment Selection and Tire Pressure Management

Selecting the right equipment makes a significant difference in preventing soil compaction. For Alberta’s diverse soil conditions, consider using tracked vehicles instead of wheeled equipment when working wet or sensitive soils. Tracks distribute weight over a larger surface area, reducing ground pressure by up to 40 percent compared to conventional tires.

When wheels are necessary, maintain proper tire pressure for your load and conditions. Lower pressures (around 70-100 kPa) reduce soil compaction in the top 30 centimeters, though consult your manufacturer’s guidelines to avoid tire damage. A 2022 study at Olds College demonstrated that reducing tire pressure from 140 to 85 kPa decreased compaction depth by nearly one-third in loam soils.

Match equipment size to field conditions. Smaller, lighter machinery causes less deep compaction, particularly valuable during spring seeding when soils hold more moisture. Consider controlled traffic farming systems that confine machinery to permanent lanes, protecting 80 percent of your field from repeated compaction. Alberta agronomist Sarah Chen notes that farmers adopting these practices often see improved water infiltration within two growing seasons, leading to better crop establishment and yields.

Remediation Strategies: Fixing Over-Compacted Soils

Mechanical Decompaction Methods

When compaction affects your soil’s ability to manage water effectively, mechanical interventions become necessary. The right approach depends on the depth and severity of compaction, as well as your specific soil type.

For surface compaction extending 15-20 centimetres deep, conventional deep tillage using a moldboard plow or chisel plow can restore soil structure. These tools work best on clay loam soils common across central Alberta, breaking up compacted layers while incorporating organic matter. However, timing matters significantly. Work your soil when moisture content sits between field capacity and slightly drier to avoid creating new compaction issues.

Subsoiling tackles deeper compaction layers, reaching 30-60 centimetres below the surface. This technique proves particularly valuable for Alberta’s heavy clay soils where hardpan layers restrict root growth and water infiltration. Dr. Myrna Melnychuk from Olds College emphasizes that subsoiling should occur when soil is dry enough to fracture rather than smear. Many Alberta farmers schedule this work during late summer or fall when conditions are optimal.

For established pastures or fields where you want to minimize surface disturbance, aerating equipment offers a gentler solution. Core aerators remove soil plugs, creating channels for air and water movement without inverting soil layers. This approach maintains existing soil biology while addressing moderate compaction.

A Peace Country grain producer shared his experience: “After subsoiling our wheat stubble in dry August conditions, we saw immediate improvements in spring water infiltration. The investment paid off in higher yields the following season.”

Remember that mechanical decompaction works best as part of a comprehensive strategy that includes reducing future compaction through controlled traffic patterns and maintaining organic matter levels.

Biological Solutions: Cover Crops and Root Systems

Nature provides powerful allies in the fight against soil compaction through strategic cover cropping. Deep-rooted varieties work like natural tillers, penetrating hardpan layers that machinery struggles to reach, all while building soil health.

Tillage radishes, also known as daikon radishes, are particularly effective for Alberta conditions. These taproots can drill down 30 to 90 centimeters, creating channels that improve water infiltration and air exchange. When they decompose over winter, they leave behind organic pathways perfect for subsequent crop roots to follow.

Cereal rye stands out as another excellent choice for Canadian growers. Its extensive fibrous root system can reach depths of 180 centimeters under favorable conditions, effectively breaking up compacted zones while scavenging nutrients that might otherwise leach away. Trevor McNaughton, a soil health specialist working with farmers near Red Deer, reports that growers using cereal rye consistently see improved water penetration rates within two seasons.

Legumes like alfalfa and sweet clover offer the dual benefit of deep roots and nitrogen fixation. Their taproots can penetrate compacted layers while adding valuable organic matter and nutrients to your soil profile.

The key to success lies in timing and diversity. Plant cover crops immediately after harvest to maximize growing time before frost. Consider mixing species to target different soil depths and provide varied organic matter. A blend of tillage radish, cereal rye, and hairy vetch, for example, creates multiple pathways through compacted zones while building soil structure for seasons to come.

Organic Matter and Soil Structure Recovery

Rebuilding soil structure after compaction requires patience and consistent organic matter management. Alberta farmers have found success by applying compost at rates of 10-20 tonnes per hectare, which introduces beneficial microorganisms and carbon that bind soil particles into stable aggregates. Manure incorporation works similarly, with aged cattle manure being particularly effective for clay-heavy soils common across the prairies.

Leaving crop residues on the field rather than removing them provides ongoing organic inputs. A Red Deer area producer shared that maintaining 30 percent residue cover improved his soil’s water infiltration by 40 percent within three growing seasons. The key is avoiding tillage immediately after residue application, allowing natural decomposition to occur.

Consider cover crops like fall rye or winter wheat between cash crops. These add root biomass that creates natural channels in compacted layers while protecting soil from erosion. Think of this approach as a long-term investment in your land’s productivity. Recovery typically takes 3-5 years, but the improvements in aggregate stability and water-holding capacity make it worthwhile for building farm resilience.

Real Results: Alberta Farmers Managing Compaction Successfully

When Tom Beckman took over his family’s 800-hectare grain operation near Lacombe in 2018, he inherited a serious problem. Years of heavy equipment traffic during wet conditions had created compaction layers that were strangling his crop potential. His canola yields had dropped to 32 bushels per acre, well below the regional average, and standing water after spring melt was becoming the norm.

“I could see the difference just walking the fields,” Tom recalls. “Some areas, you’d sink right in. Others felt like concrete. The plants were telling me something was wrong—shallow roots, uneven emergence, yellow patches that wouldn’t green up no matter how much nitrogen I threw at them.”

Tom started by mapping his problem areas using penetrometer readings and yield data from three previous seasons. The results confirmed severe compaction at 15 to 30 centimetres depth across 40 percent of his operation. Working with his local agronomist, he developed a three-year remediation plan.

The strategy combined controlled traffic farming principles with deep zone tillage in the worst affected areas. Tom invested in RTK guidance to confine wheel traffic to permanent lanes, reducing the compacted footprint from 80 percent to 25 percent of field area. In targeted zones, he used a deep ripper equipped with soil-lifting wings during optimal soil moisture conditions in fall 2019.

The investment paid dividends quickly. By 2021, water infiltration rates in treated areas improved from 12 millimetres per hour to 38 millimetres per hour. Canola yields jumped to 48 bushels per acre, and spring flooding issues virtually disappeared. Root depth measurements showed canola taproots reaching 60 centimetres compared to just 25 centimetres before treatment.

“The key was being patient and strategic,” Tom emphasizes. “We didn’t try to fix everything at once. We focused on the worst areas first and built from there. Now my crops can actually access the moisture and nutrients that were always there—they just couldn’t reach them.”

Expert Insights: What the Specialists Recommend

Leading soil scientists across the Canadian prairies are increasingly focused on precision approaches to managing compaction. Dr. Sarah Chen, a soil scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, emphasizes the importance of timing: “Our research shows that working soil at proper moisture levels reduces compaction risk by up to 60 percent. For Alberta conditions, this means waiting until soil can be formed into a ball but crumbles easily under light pressure.”

Agricultural engineer Mark Thorvaldson, who works extensively with prairie farmers, recommends investing in tire pressure monitoring systems. “We’re seeing excellent results with farmers who adjust tire pressure based on field conditions and load weight. Central tire inflation systems pay for themselves within three seasons through improved soil structure and increased yields,” he notes. His field trials demonstrate that reducing tire pressure from 170 to 100 kPa in appropriate conditions can decrease compaction depth by 40 percent.

Agronomist Dr. Jennifer Kowalski highlights emerging technologies gaining traction in Alberta. “Track systems and controlled traffic farming are no longer just for large operations. Mid-sized farms are forming equipment-sharing cooperatives to access these technologies affordably. We’re also seeing promising results with automated compaction mapping using yield monitors and soil sensors.”

The specialists unanimously recommend establishing baseline measurements before implementing changes. “You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” states Dr. Chen. “Simple penetrometer readings taken consistently across your fields provide invaluable data for decision-making.”

For remediation of existing compaction, the experts suggest a graduated approach combining deep-rooted cover crops with strategic tillage only when necessary. This biological-first strategy aligns with both economic and environmental sustainability goals while addressing the unique challenges of short growing seasons and variable moisture conditions across the prairies.

Effective soil compaction management isn’t about choosing between preventing compaction or using it strategically—it’s about understanding when and how to apply both approaches. As we’ve explored, Alberta farmers face unique challenges with soil-water dynamics, from spring moisture retention to managing heavy clay soils that are particularly susceptible to compaction damage.

The key takeaway is balance. Prevent harmful compaction by timing field operations carefully, reducing axle loads, and maintaining soil organic matter. When strategic compaction benefits your operation—such as improving seed-to-soil contact or managing excessive drainage in sandy fields—apply controlled techniques with appropriate equipment at optimal moisture levels.

Start by assessing your current practices. Walk your fields after harvest and look for compaction indicators like poor water infiltration, standing water, or restricted root growth. Consider investing in a penetrometer to measure compaction depth across different zones. These simple diagnostic steps cost little but provide valuable baseline data.

Remember that soil and water conservation is an ongoing journey, not a destination. Even small improvements—like adjusting tire pressure based on soil conditions or incorporating one cover crop into your rotation—compound over time. Many Alberta producers have seen measurable improvements in water infiltration and crop yields within just two to three seasons of implementing better compaction management.

Your soil is your most valuable asset. Take one practical step this season toward better compaction management, and build from there. Your future harvests will reflect the care you invest today.