Beneath every thriving forest and productive farm field lies an invisible partnership that’s been sequestering carbon for 400 million years. Mycorrhizal fungi form thread-like networks that connect with tree and plant roots, extending their reach up to 1,000 times while pulling carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it deep in the soil. For Alberta farmers, this natural alliance represents an untapped opportunity to enhance both soil health and carbon credit potential without requiring additional land or major equipment investments.

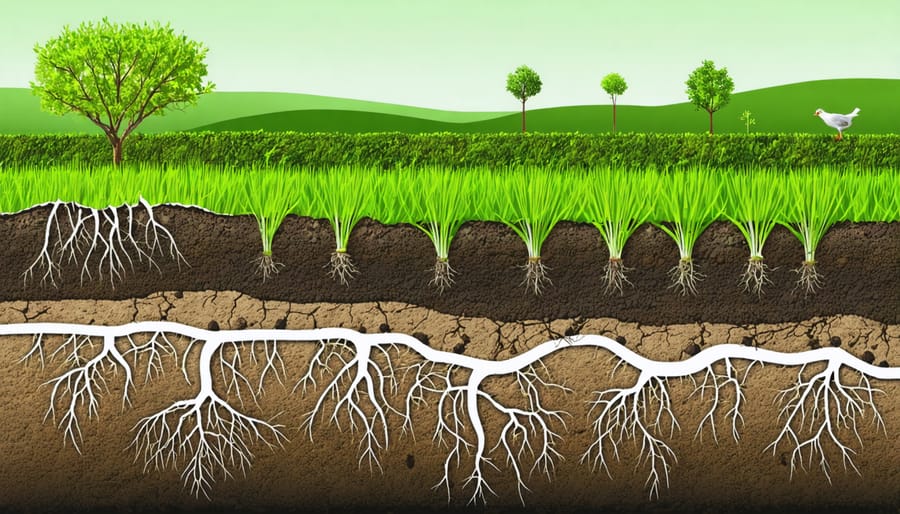

The science is straightforward: mycorrhizal fungi receive sugars from plants while delivering water, nutrients, and remarkable carbon storage capacity in return. A single gram of healthy prairie soil can contain up to 100 metres of fungal threads, each strand actively moving carbon underground where it can remain stable for decades. This biological process sequesters an estimated 5 billion tonnes of carbon globally each year, roughly equivalent to 13 percent of annual fossil fuel emissions.

Canadian farmers are already seeing measurable results. Studies from the University of Alberta demonstrate that agricultural lands with robust mycorrhizal networks store 30 to 40 percent more carbon than depleted soils, translating to potential carbon credit revenues while improving crop resilience during Alberta’s increasingly variable growing seasons. Understanding how to protect and enhance these fungal partnerships starts with recognizing what disrupts them and which management practices strengthen this underground carbon highway.

What Mycorrhizal Fungi Actually Do Underground

The Two Types That Matter for Canadian Farms

Understanding which fungi work with your trees makes all the difference when planning for carbon sequestration on your farm. Two main types of mycorrhizal fungi dominate in Alberta: ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi.

Ectomycorrhizal fungi form a sheath around tree root tips and are the primary partners for coniferous trees like white spruce, lodgepole pine, and jack pine—common species in Alberta’s boreal regions and shelterbelts. These fungi create extensive underground networks that can connect multiple trees, sometimes called “wood wide webs,” helping trees share nutrients and water while sequestering significant amounts of carbon in the soil.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi take a different approach, actually penetrating root cells to exchange nutrients. These work with most deciduous trees including trembling aspen, balsam poplar, and willow species that you’ll find in riparian areas and windbreaks across the prairies. While they don’t form the same visible networks as ectomycorrhizal types, they’re equally important for soil health and carbon storage.

The practical takeaway? If you’re managing spruce or pine shelterbelts, you’re working with ectomycorrhizal systems. For those riparian buffers with poplar and willow, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are your partners. Knowing this distinction helps you make informed decisions about soil management practices that protect these beneficial relationships. Both types contribute substantially to long-term carbon sequestration, making them valuable allies in sustainable farm management.

The Carbon Sequestration Connection

How Much Carbon Can Actually Be Stored

Understanding the real-world numbers helps set realistic expectations for your operation. Research from Canadian agricultural studies shows that mycorrhizal-enhanced systems can sequester between 0.5 to 2 tonnes of carbon per hectare annually in prairie soils, compared to 0.2 to 0.8 tonnes in conventional systems without active fungal management.

On Alberta farmland, the storage capacity varies significantly based on your starting point. Degraded soils with low organic matter typically see the most dramatic improvements. Dr. Sarah Chen from the University of Alberta’s Department of Renewable Resources explains that fields with established mycorrhizal networks can store up to 30% more carbon in the top 30 centimetres of soil compared to fields managed with intensive tillage and limited fungal activity.

The math works out favourably for prairie farmers. A 65-hectare operation implementing mycorrhizal-friendly practices could potentially sequester an additional 65 to 130 tonnes of carbon annually compared to conventional methods. Over a decade, that represents 650 to 1,300 tonnes of stored carbon, which translates to meaningful participation in carbon credit programs.

However, these aren’t overnight results. Most Alberta farmers report measurable improvements in soil carbon within three to five years of transitioning to mycorrhizal-supportive practices. The key is consistency in maintaining conditions that allow fungal networks to thrive.

It’s worth noting that carbon storage isn’t linear. Your soil has a saturation point, typically reached when organic matter levels hit 4-6% in prairie conditions. Once you approach this threshold, storage rates plateau, but the existing carbon remains locked in place as long as the fungal networks stay intact. This makes preservation of established networks just as important as building new ones.

Why This Matters for Alberta Farmers Right Now

While carbon credits offer exciting financial opportunities, the benefits of mycorrhizal fungi extend far beyond those payments, delivering practical improvements that directly impact your bottom line today.

Let’s talk about soil structure first. These fungal networks act like natural glue, binding soil particles together and creating stable aggregates. For Alberta farmers dealing with heavy clay soils or erosion-prone fields, this means improved water infiltration and reduced runoff. When spring melt or summer storms hit, you’ll see less soil washing away and more moisture staying where your trees and crops need it most.

Speaking of moisture, drought resistance has become increasingly critical across the prairies. Mycorrhizal fungi extend your trees’ root systems by up to 1,000 times, reaching water and nutrients far beyond what roots can access alone. During Alberta’s dry spells, this expanded network can mean the difference between stressed, struggling trees and healthy growth. Many farmers incorporating trees into their operations report better survival rates and faster establishment when mycorrhizal relationships are present.

The fertilizer savings alone can justify the effort. These fungi specialize in scavenging phosphorus, often the most limiting nutrient in our soils. They’re remarkably efficient at accessing forms of phosphorus that plants simply cannot reach on their own. Research from Canadian agroforestry systems shows fertilizer reductions of 20 to 30 percent while maintaining or improving tree health. With current input costs, that translates to real money staying in your pocket each season.

For those exploring agroforestry systems, mycorrhizal fungi create synergies between your trees and adjacent crops. The fungal networks don’t stop at tree roots – they can connect multiple plant species, facilitating nutrient sharing and improving overall system resilience. Shelterbelt trees with robust mycorrhizal partnerships grow faster, provide better windbreak protection sooner, and support healthier understory vegetation.

The health benefits compound over time. Trees with strong fungal partnerships show increased resistance to diseases and environmental stresses. They’re better equipped to handle temperature fluctuations, nutrient imbalances, and pest pressures. This means lower mortality rates, reduced replacement costs, and more reliable performance from your agroforestry investments.

These aren’t theoretical benefits. Farmers across Alberta are already seeing results: healthier trees, improved soil conditions, and reduced input costs. When you combine these immediate, tangible advantages with potential carbon credit revenue, supporting mycorrhizal fungi becomes one of the smartest management decisions you can make for your land’s long-term productivity and profitability.

Setting Up Mycorrhizal Systems on Your Land

Choosing the Right Trees for Your Property

Selecting tree species that form strong mycorrhizal partnerships is essential for maximizing carbon sequestration and overall tree health in Alberta’s climate. Native and cold-hardy species have evolved alongside local mycorrhizal fungi communities, making them naturally compatible partners for regenerative agroforestry systems.

For shelterbelts and windbreaks, consider hybrid poplar, which forms robust ectomycorrhizal associations and grows rapidly in Alberta conditions. White spruce and lodgepole pine are excellent conifer options that partner with ectomycorrhizal fungi while providing year-round wind protection. These species can sequester significant carbon while improving soil structure through their fungal networks.

Deciduous species like trembling aspen, bur oak, and Manitoba maple work exceptionally well in mixed plantings. Bur oak, though slower-growing, develops extensive mycorrhizal networks that can support surrounding plants for decades. Manitoba maple offers quick establishment and hardy performance across the prairie provinces.

For edible and productive shelterbelts, saskatoon berries and haskap form arbuscular mycorrhizal relationships and thrive in Alberta’s growing zones. These shrubs provide both ecosystem services and market opportunities.

When planning your planting scheme, aim for diversity. Mixed-species shelterbelts create more extensive mycorrhizal networks than monocultures, enhancing carbon storage capacity by 20 to 40 percent. Space trees 2 to 4 metres apart in rows, with 4 to 6 metres between rows for equipment access and optimal root development.

Inoculation Methods That Actually Work

Getting mycorrhizal fungi established in your soil is straightforward, whether you’re planting new seedlings or working with mature trees. The key is choosing quality products and applying them at the right time.

For new plantings, the most effective approach is root dipping. Mix granular mycorrhizal inoculant with water to create a slurry, then dip bare-root seedlings before planting. This ensures direct contact between fungi and roots. If you’re planting container trees, sprinkle inoculant directly into the planting hole, ideally 5-10 grams per tree depending on size, and ensure the roots touch the inoculant layer.

Established trees require a different strategy. Create injection points using a soil probe or auger at the tree’s drip line, spacing holes roughly 30 centimetres apart. Mix granular inoculant with water and pour into these holes, allowing the fungi to colonize the active root zone. For orchards or shelterbelts, some Alberta farmers broadcast inoculant and incorporate it into the top 10-15 centimetres of soil during cultivation.

Canadian suppliers like Plant Health Care and Reforestation Technologies International offer products specifically formulated for prairie conditions. Local agricultural co-ops across Alberta increasingly stock these products, making sourcing convenient. When purchasing, verify the product contains live spores and matches your tree species, since ectomycorrhizal products suit conifers while endomycorrhizal types work better for most deciduous trees.

Timing matters too. Apply inoculants during cool, moist conditions in spring or fall when root growth is most active, maximizing colonization success.

Protecting Your Existing Fungal Networks

Once you understand the value of mycorrhizal fungi, protecting these existing networks becomes a priority. The good news is that relatively simple adjustments to your soil management practices can preserve and even strengthen these beneficial relationships.

Reducing or eliminating tillage is one of the most effective protective measures. Every time you turn the soil, you physically break the delicate fungal threads that connect trees to the broader network. Many Alberta farmers have transitioned to no-till or reduced-till systems and report improved soil structure within just a few seasons. If you’re managing orchards, pastures, or shelterbelts, minimizing soil disturbance around tree root zones is particularly important.

Your fertilizer choices matter too. While plants need nutrients, excessive synthetic nitrogen and phosphorus applications can actually discourage trees from maintaining their fungal partnerships. When nutrients are readily available in simple forms, trees have less incentive to invest energy in mycorrhizal relationships. Consider soil testing before applying fertilizers and aim for balanced, gradual nutrient release.

Similarly, certain fungicides and broad-spectrum pesticides can harm beneficial fungi along with their targets. When pest management is necessary, choose products with minimal impact on soil biology and apply them strategically rather than as blanket treatments.

Finally, maintaining organic matter through practices like mulching, cover cropping, and leaving crop residues feeds the entire soil food web, including mycorrhizal fungi. These organisms thrive in biologically active soils rich in carbon.

Real Results from Canadian Farms

When Jim Patterson first considered integrating mycorrhizal fungi into his mixed farming operation near Red Deer, Alberta, he wasn’t sure what to expect. Like many farmers in the region, he’d heard about the carbon sequestration potential but wanted proof it could work on Canadian soil before making any significant changes.

In spring 2021, Patterson partnered with researchers from the University of Alberta to establish a three-year trial on 40 hectares of his property. The project focused on introducing mycorrhizal fungi to a combination of native trees and shelterbelts that he’d been planning to expand anyway.

“We started with white spruce and trembling aspen along the north edge of our fields,” Patterson explains. “The inoculant cost was around $15 per tree, which seemed steep at first, but the researchers helped us access provincial funding that covered about 60 percent of the initial investment.”

The implementation process took approximately two weeks during the planting season. Patterson’s crew applied granular mycorrhizal inoculant directly into the planting holes, ensuring good contact with root systems. They also amended soil with minimal tillage to avoid disrupting existing fungal networks in adjacent areas.

The first growing season brought unexpected challenges. A late spring frost damaged some seedlings, and Patterson worried the investment might not pay off. However, by fall 2021, survival rates told a different story. Trees with mycorrhizal treatment showed 89 percent survival compared to 71 percent in control plots without inoculant.

By year two, measurable differences became even more apparent. Treated trees demonstrated 34 percent greater height growth and notably improved drought resistance during Alberta’s dry summer of 2022. Soil carbon measurements taken at 18 months showed a 12 percent increase in organic carbon content within the root zones of mycorrhizal-treated trees.

“The root development was remarkable,” Patterson notes. “When we did some test excavations, the mycorrhizal trees had root systems almost twice the size of untreated ones.”

Most significantly for Patterson’s operation, the enhanced carbon sequestration qualified his farm for Alberta’s carbon offset program. The preliminary assessment indicated potential credits worth approximately $8,000 annually once the trees reach full maturity in years five through seven.

Patterson now plans to expand mycorrhizal integration across another 80 hectares, incorporating the practice into his regular shelterbelt maintenance. His advice to other farmers is straightforward: start small, document everything, and connect with local agricultural extension services who understand regional soil conditions and can provide guidance specific to Alberta’s climate.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even well-intentioned farmers can inadvertently harm mycorrhizal networks through common management practices. Understanding these pitfalls helps you protect your investment in soil health.

Excessive tillage ranks as the number one fungi killer. Deep cultivation physically tears apart the delicate hyphal networks that took months or years to establish. If you’ve recently tilled and then inoculated, you’re essentially starting from scratch. Alberta farmer Tom Henderson learned this lesson after repeatedly disking his shelter belt areas and wondering why tree growth remained sluggish. The solution? Minimize soil disturbance where possible, or time inoculation for after your last tillage pass when establishing new plantings.

Overapplication of synthetic fertilizers, particularly phosphorus, can actually suppress mycorrhizal colonization. When trees receive abundant nutrients directly, they reduce their investment in fungal partnerships. This doesn’t mean eliminating fertilizer entirely, but rather conducting soil tests first and applying only what’s truly needed. Aim for soil phosphorus levels between 15-30 ppm for optimal mycorrhizal activity.

Many farmers expect dramatic results within weeks of inoculation. Setting realistic timelines prevents disappointment. Visible growth improvements typically appear 6-12 months after application for younger trees, while mature trees may take even longer to show measurable responses. The fungi are working underground long before you see above-ground changes.

Timing errors also derail success. Inoculating during drought stress or extreme heat reduces fungal establishment. Spring and fall applications, when soil moisture is adequate and temperatures moderate, yield better colonization rates. If you’ve already inoculated during poor conditions, a follow-up application the next season can improve results.

Remember, building soil biology is a long-term investment, not a quick fix.

Making It Financially Worthwhile

Investing in mycorrhizal fungi partnerships offers Canadian farmers multiple pathways to financial returns that extend well beyond immediate crop yields. The most promising opportunity lies in carbon markets, where enhanced soil carbon storage translates directly into revenue.

Through programs like the soil carbon credits market, Alberta farmers can now monetize the carbon sequestration happening beneath their fields. Mycorrhizal networks significantly boost this potential by storing carbon in both fungal biomass and soil aggregates. Recent projects in central Alberta have demonstrated that farms with established mycorrhizal systems can sequester an additional 0.5 to 1.5 tonnes of carbon per hectare annually, generating $15 to $45 per hectare in credit revenues at current market rates.

Beyond carbon credits, the operational cost savings are substantial. Farmers report reducing phosphorus fertilizer applications by 20 to 40 percent once mycorrhizal networks are established, as the fungi efficiently mine soil phosphorus that would otherwise remain unavailable to plants. This translates to savings of $25 to $50 per hectare annually on fertilizer costs alone. Water use efficiency improvements can reduce irrigation expenses by similar margins in areas where supplemental watering is necessary.

Federal and provincial support continues to expand. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Agricultural Climate Solutions program provides cost-share funding for adopting practices that enhance carbon sequestration, including cover cropping and reduced tillage systems that support mycorrhizal development. The Canadian Agricultural Partnership also offers provincial programs specific to Alberta that support agroforestry initiatives and sustainable soil management.

The long-term economic picture grows even more compelling. Farms that invest in mycorrhizal-friendly practices today are building soil capital that increases land value, improves drought resilience, and positions operations favorably as carbon pricing mechanisms evolve. Industry experts suggest that within five years, carbon-rich soils may command premium pricing in farmland markets, rewarding early adopters who prioritized biological soil health.

Integrating mycorrhizal fungi into your farming operation represents a practical step toward building soil health, improving crop resilience, and contributing to meaningful climate action right here in Alberta. The partnership between these fungi and your trees or crops isn’t just good science—it’s a proven strategy that enhances carbon sequestration, reduces input costs, and strengthens your land’s productivity for the long term.

You don’t need to overhaul your entire operation overnight. Start small: test mycorrhizal inoculation on a portion of your shelterbelts or agroforestry plots this season. Monitor the results, share your observations with neighbours, and expand as you gain confidence. Many Alberta farmers have already seen measurable improvements in tree establishment rates and soil structure within just a couple of growing seasons.

The financial incentives available through carbon offset programs and sustainable agriculture initiatives make this transition more accessible than ever. Connect with your local agricultural extension office or regional farming networks to explore funding opportunities specific to your area. These resources exist to support farmers like you who are willing to implement practices that benefit both your operation and the broader environment.

Remember, building a thriving mycorrhizal network takes time—typically three to five years for full establishment—but the investment pays dividends through reduced fertilizer needs, improved drought tolerance, and enhanced carbon storage. Your commitment to these practices strengthens not only your farm but also contributes to Alberta’s agricultural leadership in climate-smart farming. Take that first step today, and join the growing community of producers investing in soil health for future generations.