Harness the ancestral wisdom of Indigenous agricultural practices by integrating natural water flow patterns, companion planting strategies, and layered growing systems into modern Canadian farm designs. Traditional Three Sisters planting methods – combining corn, beans, and squash – demonstrate how permaculture’s core principle of interconnected systems has sustained communities across Alberta’s diverse growing zones for generations.

Working with nature rather than against it transforms challenging agricultural landscapes into resilient food-producing ecosystems. From the windswept prairies to sheltered river valleys, successful permaculture design adapts universal principles to local conditions – maximizing sunlight capture through thoughtful placement, creating beneficial microclimates with strategic windbreaks, and building soil fertility through perennial polycultures.

This regenerative approach helps Alberta farmers reduce inputs while increasing yields, drawing on time-tested Indigenous knowledge to develop climate-resilient growing systems. By understanding how natural ecosystems function and applying these patterns to farm design, producers can create abundant, self-sustaining landscapes that thrive in our unique Canadian growing conditions while honoring the agricultural heritage of this land.

Traditional Indigenous Land Management in Alberta

Three Sisters Companion Planting

The Three Sisters companion planting system, developed by Indigenous peoples across North America, stands as one of the most successful examples of permaculture principles in action. In this traditional method, corn, pole beans, and squash work together in perfect harmony, each supporting the others’ growth and development.

The tall corn stalks provide natural trellises for climbing beans, while the beans fix nitrogen in the soil, benefiting all three plants. The large squash leaves spread across the ground, creating living mulch that conserves soil moisture and suppresses weeds. This groundcover also helps prevent soil erosion during Alberta’s intense summer storms.

For Alberta farmers, this system offers particular advantages. The short growing season means maximizing space and resources is crucial. When properly implemented, the Three Sisters method can yield up to 20% more food per acre compared to monoculture plantings of these crops. Local agricultural trials have shown this system performs exceptionally well in the rich black soils of central Alberta, though timing and spacing must be adjusted to account for our northern climate and shorter frost-free period.

Water Conservation Methods

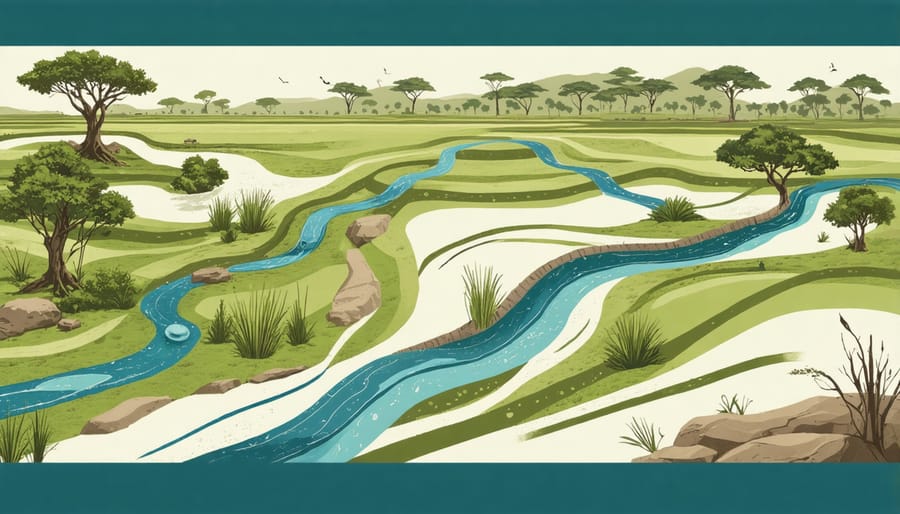

In the heart of Alberta’s diverse landscapes, effective water conservation techniques have become increasingly vital for sustainable agriculture. Drawing from Indigenous knowledge, modern permaculture designers integrate swales, berms, and rainwater harvesting systems to maximize water retention. These methods work particularly well in Prairie regions, where moisture conservation is crucial during dry periods.

Keyline design, a system that follows natural contours of the land, helps direct water flow to where it’s needed most. Many Alberta farmers have found success with this approach, reporting up to 30% reduction in irrigation needs. Combined with mulching and strategic plant placement, these systems create self-sustaining water cycles that benefit the entire farm ecosystem.

Storage solutions like dugouts and rain barrels provide reliable water reserves during drought periods. Some farmers enhance these systems with gravity-fed irrigation, reducing energy costs while ensuring consistent water distribution. The key is to work with the land’s natural features, creating interconnected systems that capture, store, and distribute water efficiently throughout the growing season.

Core Permaculture Principles in Indigenous Systems

Working with Natural Patterns

In Alberta’s diverse landscapes, understanding and working with natural patterns has been a cornerstone of successful farming for generations. Indigenous communities, particularly the Blackfoot and Cree peoples, have long recognized the importance of aligning agricultural practices with seasonal rhythms and natural cycles.

These traditional knowledge systems teach us to observe and respond to natural indicators, such as when certain birds return in spring or when specific wildflowers bloom, to time our planting and harvesting activities. For example, many Indigenous communities traditionally planted when the wild roses began to bud, knowing this signaled the end of frost risk.

Modern permaculture in Alberta can benefit greatly from this wisdom. By watching wind patterns, we can better position windbreaks and shelter belts. Understanding local water flow helps in designing swales and catchment systems that work with the land’s natural contours. Even animal behavior patterns provide valuable insights – deer and elk movement patterns can indicate natural corridors that should be preserved or enhanced.

The key is observation and patience. Spend time understanding your land through all seasons. Notice where snow drifts form in winter, where water pools in spring, and how summer winds affect different areas. These patterns inform smart design decisions that work with nature rather than against it, reducing the need for intensive intervention and creating more resilient agricultural systems.

Zero-Waste Approaches

In permaculture, the concept of zero waste draws inspiration from natural ecosystems where every output becomes an input for another process. On Alberta farms, this approach transforms what might be considered “waste” into valuable resources, creating closed-loop systems that benefit both the environment and farm economics.

Consider how traditional Indigenous farming practices have long demonstrated this principle through the careful use of every part of harvested crops and animals. Today, we can apply these time-tested methods alongside modern innovations. For example, livestock manure becomes valuable compost for crop fields, while crop residues serve as animal bedding or mulch for soil protection.

Many Alberta farmers are successfully implementing zero-waste systems. The McKenzie Family Farm near Red Deer, for instance, uses food scraps from local restaurants to feed their chickens, whose manure then fertilizes their market garden. The resulting vegetable trim gets composted or fed back to livestock, completing the cycle.

Practical zero-waste strategies include:

– Creating compost systems that process all organic matter

– Using grey water from washing facilities to irrigate non-food plants

– Converting agricultural byproducts into mulch or building materials

– Establishing partnerships with local businesses for resource sharing

By viewing waste as a resource out of place, farmers can reduce operational costs while building soil health and supporting local ecosystems. This approach not only honours traditional agricultural wisdom but also creates resilient farm systems for the future.

Practical Applications for Alberta Farms

Soil Health Management

Indigenous communities across Canada have long understood the delicate balance required for healthy soil systems. By integrating these traditional soil building methods with modern permaculture practices, Alberta farmers are discovering powerful ways to enhance soil health while honoring ancestral wisdom.

Key to this approach is the Three Sisters method of companion planting, where corn, beans, and squash work together to build soil structure. The corn provides support, beans fix nitrogen, and squash creates living mulch that retains moisture and suppresses weeds. Many Alberta farmers have adapted this technique by incorporating cold-hardy varieties suited to our climate.

Modern soil management also benefits from the Indigenous practice of minimal soil disturbance. Rather than aggressive tilling, permaculture designs emphasize sheet mulching and targeted amendments. Local success stories include the Thunder Creek Farm near Red Deer, where implementing these methods has increased organic matter by 2% over five years.

Natural soil amendments like spruce needle mulch and aged manure mirror traditional practices while meeting current organic certification standards. Combined with cover cropping and planned grazing patterns, these methods create resilient soil systems that withstand both drought and excess moisture – a crucial advantage for prairie farmers facing climate variability.

Biodiversity Enhancement

In the heart of Canadian permaculture, biodiversity enhancement draws inspiration from traditional Indigenous practices while incorporating modern ecological understanding. The Blackfoot people’s Three Sisters planting method – combining corn, beans, and squash – demonstrates how companion planting naturally increases soil fertility and creates beneficial insect habitats.

Creating diverse ecosystems starts with layered planting, mimicking natural forest structures. In Alberta’s climate, this might include tall trees like saskatoons providing shelter, medium-height plants like haskap berries, and ground covers like native strawberries. This vertical stacking maximizes space while creating multiple wildlife habitats.

Edge zones, where different ecosystems meet, are particularly important for biodiversity. These transition areas, such as where forest meets meadow, typically support more species than either habitat alone. Alberta farmers often maintain these edges by creating hedgerows or windbreaks using native species like wolf willow and chokecherry.

Water features, even small dugouts or seasonal wetlands, significantly boost biodiversity. These areas attract beneficial insects, amphibians, and birds that help with natural pest control. Many Alberta farmers maintain small ponds with cattails and bulrushes to support local wildlife while providing natural water filtration.

Including native flowering plants throughout the design supports essential pollinators. Plants like golden rod, yarrow, and wild bergamot not only attract beneficial insects but also provide medicinal value and create resilient plant communities that thrive in our local climate.

Climate Resilience Strategies

Indigenous communities across Canada have developed sophisticated climate resilience strategies over thousands of years, offering valuable insights for modern permaculture practitioners. The Blackfoot people of southern Alberta, for example, traditionally planted in natural depressions where snow and rain naturally collect, creating microclimate buffers against drought conditions.

One key approach is the Three Sisters companion planting method, where corn, beans, and squash are grown together. This technique, pioneered by Indigenous peoples, creates natural wind breaks and moisture retention systems, particularly valuable in Alberta’s chinook-prone regions. The tall corn stalks shield younger plants from harsh winds, while broad squash leaves reduce soil moisture evaporation.

Weather pattern adaptation also involves careful observation of natural indicators. Many Indigenous communities track bird migration patterns, plant flowering times, and insect behavior to anticipate weather changes and adjust planting schedules accordingly. This traditional knowledge aligns perfectly with permaculture’s emphasis on natural observation and adaptation.

Modern Alberta farmers are increasingly combining these time-tested methods with contemporary techniques. For instance, some are creating shelterbelts using native species like wolfwillow and chokecherry, positioned according to traditional Indigenous knowledge of wind patterns. These natural windbreaks protect crops while providing habitat for beneficial wildlife, demonstrating how ancient wisdom can enhance modern farming resilience.

As we’ve explored throughout this guide, permaculture design principles offer powerful tools for creating resilient and sustainable agricultural systems here in Alberta. By working with nature rather than against it, we can build farms that are both productive and regenerative for generations to come.

Remember that successful implementation starts with careful observation of your specific land, climate conditions, and available resources. Begin with small, manageable projects like establishing windbreaks or implementing water harvesting systems. These initial steps will help you gain confidence while minimizing risk as you learn.

Connecting with local permaculture groups and experienced practitioners can provide invaluable support and knowledge sharing. The Alberta permaculture community continues to grow, offering workshops, mentorship opportunities, and hands-on learning experiences throughout the province.

Consider documenting your journey as you implement these principles. Your experiences can contribute to our collective understanding of how permaculture practices adapt to our unique Canadian context. Whether you’re managing a large farm operation or working with a small plot, these design principles can be scaled to meet your needs.

Take time to develop your master plan, but don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. Start where you are, use what you have, and remember that permaculture is about progressive improvement rather than overnight transformation. Your efforts today will help build a more sustainable and resilient agricultural future for Alberta.